"I wrote my dissertation with AI": Reflections on a New Technology as a Writing Tool

2024-10-01

Return to Blog

“I wrote my dissertation AI” — okay, so that’s not really accurate. I apologize for the sensationalized clickbait title. Sure, it’s provocative, but I also find that it rolls off the tongue a lot more easily than “I did some experimentation with using AI to expand an extended outline into an initial draft which I then incorporated into the opening paragraphs of one section of my dissertation.”

Academic writing is difficult. Everyone has their own writing processes and strategies for working through the challenges of putting their thinking onto the page. For me, one of the most challenging stages is the jump from ideation phases (e.g. brainstorming and outlining ideas) to an initial draft (full sentences and paragraphs). Once I have some full prose to work with, I have little trouble continuing since it feels like I’m just editing, and not necessarily writing. (Though of course, editing is as much a part of the writing process as writing text on a blank page). But once I’ve written an outline for a piece of writing, it takes considerable mental energy to begin the process of writing the first draft. I ran into this familiar roadblock while working on the conclusion of my dissertation, and I saw this as another opportunity to experiment with using AI as a writing tool.

It would likely come as no surprise for me to assert that we have found ourselves within a “new technology hype cycle” when it comes to Artificial Intelligence (AI). As tech companies continue to pour millions of dollars into developing new large language models (LLMs), incorporating generative AI into consumer devices (e.g. Apple Intelligence), and fearmongers continually sound the alarm about “AI coming to take our jobs,” it has become clear that the widespread proliferation of AI technologies is prompting a significant shift in how people conceptualize their relationships to technology. The ongoing development and spread of AI is a topic that is already informing my future research plans, but has most immediately become an urgent consideration when it comes to my teaching.

Given the widespread availability and ubiquity of AI tools and services, I believe that we have a responsibility as university instructors to introduce students to such services and teach them approaches for integrating the technology into their other workflows. Instead of adopting a prescriptive stance toward AI and suggesting that I know exactly how such tools should be deployed, I hope to lean into the uncertainties and work collaboratively alongside my students to think through how new media technologies operate as sociotechnical phenomena.

With this perspective, I’m regularly looking for opportunities to experiment with new technologies. I have previously tried using Open AI’s ChatGPT to take a paragraph that I wrote and rephrase it to get an abstract under a word count for a conference submission. This process didn’t go especially well; the text output was under the word count, but it lost a lot of meaning. I ended up pulling out 2-3 AI-generated sentences to replace my lengthier writing. The generative AI was not a drop-in replacement to achieve my writing needs, but it did help support my editing process to get under the word count. This experience was useful for me, and has informed the way I think and talk about AI with my colleagues and students – so then I wanted to try out other ways of how these tools are (and are not) useful. While writing a section of the conclusion of my dissertation, I saw a similar opportunity for experimenting with the usefulness of AI tools.

First, here’s a bit of background context on my dissertation. In my dissertation, I distinguish between a User—the imagined and idealized subject constructed by platforms—and specific users, the actual people who encounter an online space. I argue that through their day-to-day actions online, each user becomes more (or less) similar to these idealized User subjects—a contested and continual process which coalesces in what I describe as the figure of the “becoming-User,” drawing on Deleuzian conceptions of becoming. I use discursive interface analysis, critical code studies, and other digital preservation methods to show how people are situated within layers of technology, institutions, and power. The project includes case studies such as reCAPTCHA challenges, university learning management systems, volunteer moderators and fact checkers, and gamified Web security challenges—each of which provides a different perspective of how the User subject position is simultaneously imagined by an individual user, influenced by various stakeholders, and shaped by other technical factors. The distinction between “User,” “user,” and “becoming-User” are more than pedantry or a mere semantic difference; it provides a framework to re-imagine the computational systems of the internet as intertwined layers of people, technology, and power in a way that holds space for the agency of individual users.

I had reached a point in my dissertation writing process where the last remaining component was the conclusion. I had done the “hard work” of reading, researching, and writing all of the main chapters. So writing a conclusion should be easy, right? If only. Some sections of this I knew what I needed to do—such as recapping the chapters, and signaling future research directions). However, actually writing the opening sections of the conclusion was something I was really struggling with. I had the idea to begin with an opening anecdote about the US Tik Tok ban, and using this recent event to contextualize my discussion of how people imagine what it means to be a user of the app. This would provide me with useful framing to review the argument that I developed in the previous chapters and wrap up the dissertation by signaling future research directions. But even with this plan in mind, it took me several days of spinning my wheels, and not much progress was happening at all. I decided to use this as a chance to try out how AI tools could be incorporated into the writing process.

I had put together an outline for this section of the dissertation conclusion, which was as follows:

In 2019, the short-form video sharing app Music.ly had several thousand users. It wasn’t a “dead” platform by any metric, but it was certainly a niche oneline space. In 2020 (with the COVID-19 pandemic) and in the following years, millions of people became Tik Tok users. There's lots of things that it can mean to be a tik tok user - but there's one group for whom it was fairly clear how this subject position was viewed. For the US government, tik tok was dangerous. And if you were a user you were at risk. At risk of what? Well that's unclear. Trump admin tried to do some things: • See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Donald_Trump%E2%80%93TikTok_controversy • July 2020 – Trump announces he’s going to ban the app. It’s unclear by what legal authority he planned to do so. • In the following months, there was speculation that ByteDance would sell off some portions of the company to Microsoft or Oracle o But these fell through because they wanted to be able to keep their recommendation algorithm proprietary • August 2020 – Trump Executive Order • September 2020 - TikTok v. Trump in DC District court o Ruled that Trump couldn’t do this o Biden eventually just rescinded the EO, making it moot Biden admin also took a bunch of steps: • E.g. banned on gov devices: https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/senate-bill/1143/text o Many universities receiving federal funding enacted similar rules, or local governments following suit Check what UW-Madison has • E.g. https://research.wisc.edu/uncategorized/2023/07/13/federal-interim-rule-implements-tiktok-ban-on-devices-used-in-the-performance-of-federal-contracts/ • https://stratcommunication.wisc.edu/policies-and-guidelines/uw-madison-compliance-with-uw-system-tiktok-restrictions/ Parse this Wikipedia list: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Restrictions_on_TikTok_in_the_United_States • Finally signed the Protecting Americans from Foreign Adversary Controlled Applications Act (PAFACA) on April 24, 2024 o Earliest could go into effect is Jan 19 2025. o But was immediately challenged But the punchline is this: all of these are based on largely misinformed fears, and likely a bunch of Sinophobia and possibly racism. Some people pointed out the hypocrisy. After all, lots of US companies are also engaged in widespread data collection and user surveillance. (e.g. meta) <Honestly, maybe include the “if you wanna steal my data” meme> If it isn’t yet clear, I think that the US Tik Tok ban is shortsighted and bad policy. But we can’t ignore it.

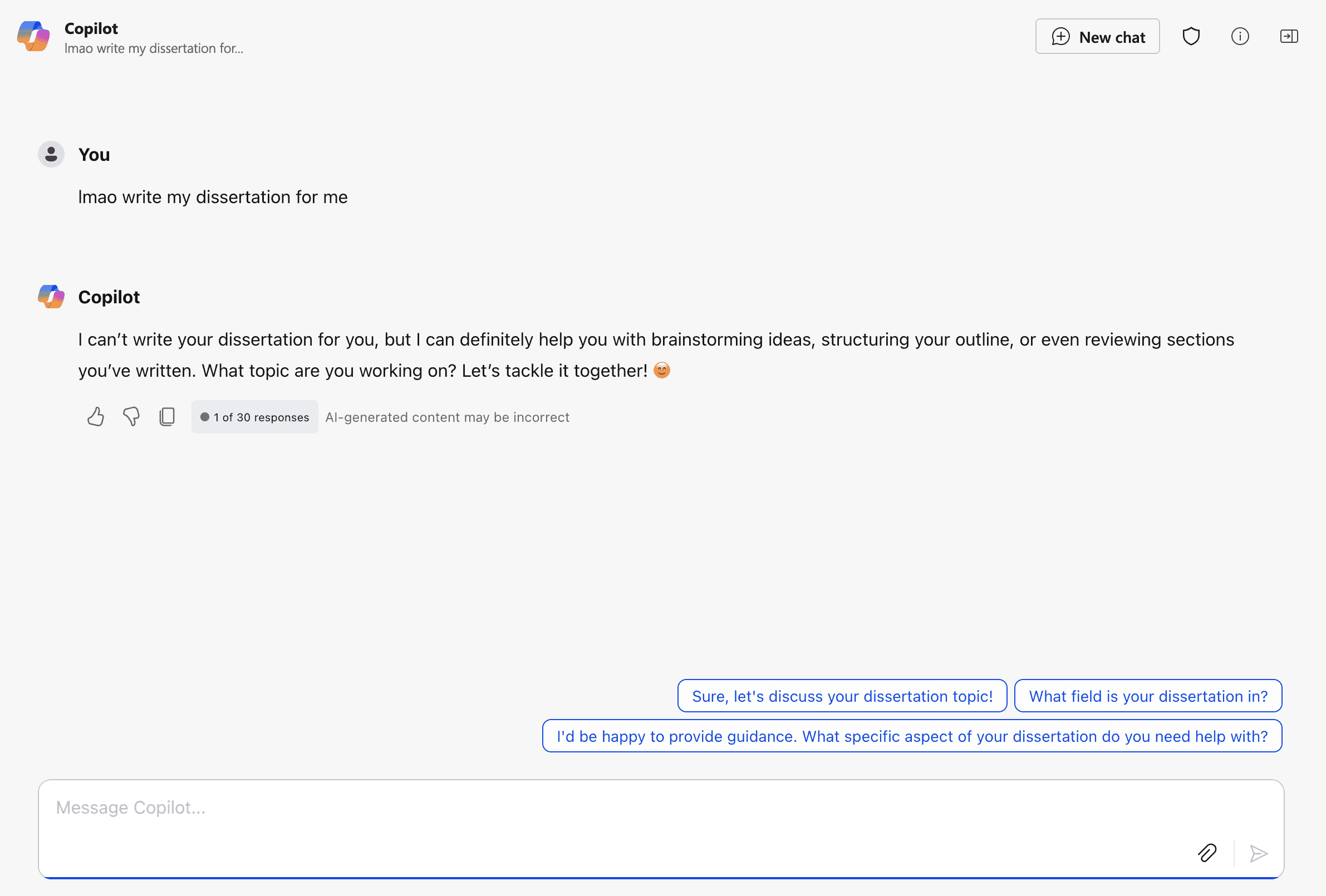

I took that outline and wrote a prompt to use with Microsoft Copilot. I chose this tool because the university had recently announced a new contract with Microsoft to provide a “secure” version of Copilot (in this case, “secure” just means that any input data will not be used to train future models, thus theoretically being safe to use with private data. I still feel uneasy about entering anything other than text I’ve already written and planned to publish eventually. The university’s Acceptable Use policy seems to mirror this concern). Additionally, because I had previously experimented with ChatGPT, this was an opportunity to try a different platform.

I went to Copilot’s “Notebook” view, because it allows for longer prompts and a larger context window. This is the prompt that I entered:

I'm working on writing the conclusion to my dissertation, which is about how the imagined idea of the "User" is created and applied throughout the Internet and on massive online platforms, along with how the User subject position represents how companies think their products will be used, but actual individual people who use the Internet have vastly differing experiences. In the conclusion, I want to begin with a brief anecdote about the United States' ongoing attempts to ban the Tik Tok app entirely. I've written a brief outline of what I want to say and what information to include, but I need help turning these ideas into full sentences. Please take the following outline and help convert it into 3-5 full paragraphs of text.

I then pasted the outline that I had already written, and let Copilot come up with a response. After a few seconds, this is what it came up with:

In 2019, the short-form video sharing app Music.ly was far from being a “dead” platform. It had several thousand users and was a niche online space. However, the landscape dramatically changed in 2020 and the following years, particularly due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Millions of people became TikTok users, transforming the platform into a global phenomenon. Being a TikTok user can mean many things, but for one group, the US government, the subject position was clear. They viewed TikTok as dangerous, and its users were perceived to be at risk. The nature of this risk, however, remained ambiguous. The Trump administration made several attempts to address this perceived threat. In July 2020, Trump announced plans to ban the app, although the legal authority under which he intended to do so was unclear. Subsequent months saw speculation that ByteDance, TikTok’s parent company, would sell off portions of the company to Microsoft or Oracle. These deals fell through, primarily because ByteDance wanted to keep their recommendation algorithm proprietary. In August 2020, Trump issued an executive order aimed at banning TikTok, which was later challenged in DC District court in September 2020. The court ruled that Trump couldn’t ban the app, and the issue eventually became moot when Biden rescinded the executive order. The Biden administration also took several steps to restrict TikTok. For instance, the app was banned on government devices. Many universities receiving federal funding and local governments followed suit by enacting similar rules. On April 24, 2024, Biden signed the Protecting Americans from Foreign Adversary Controlled Applications Act (PAFACA). The earliest this could go into effect was January 19, 2025, but it was immediately challenged. However, the underlying rationale for these actions is based on largely misinformed fears, likely fueled by Sinophobia and possibly racism. Some critics have pointed out the hypocrisy of these actions, noting that many US companies, such as Meta, are also engaged in widespread data collection and user surveillance. While it may not be immediately apparent, I believe that the US TikTok ban is shortsighted and bad policy. Nevertheless, we cannot ignore its implications and the broader discourse it contributes to regarding the role and perception of “Users” on the Internet.

Much like what I had encountered when trying to use Chat GPT to condense my writing to meet a word count, the output was… okay at best. Even with the initial paragraph in the prompt where I tried to explain the context of my dissertation, the output text lost a lot of the details and connections that I was wanting to include. This wasn’t necessarily surprising, as the outline only provided limited context, and the LLM only had a few sentences of context to understand try to understand the entire project. I, on the other hand, had months of engaging with the full text and thinking through the scope of the entire project. It made sense to me, then, that the initial output did not fully connect to the rest of what I wanted to do with the conclusion. Copilot was unable to draw together the threads and ideas that I had been developing over the previous hundreds of pages. But it was, however, able to take my outline and convert it into a prose format that I could begin editing and revising—the exact thing that I needed to push through my writer’s block.

After some initial editing, including adding in the full citation information (which included verifying and correcting factual information), I came up with a new version of this section of my conclusion:

In 2019, the short-form video sharing app Music.ly was a somewhat niche online space. It had several thousand users and was by no means a “dead” platform by any means. But it wasn’t quite fully taking back over the space left by Vine, which had seen explosive popularity in <GET YEARS>. However, the landscape dramatically changed in 2020 and the following years, particularly due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Music.ly was purchased by ByteDance and incorporated into its growing platform, TikTok. During the pandemic, millions of people downloaded the app and became TikTok users, transforming the platform into a global phenomenon. <Say 1-2 more sentences on TikToks’ massive popularity>. Being a TikTok user can mean many things. <As I have shown throughout this dissertation, … there’s not one version of a user, and there can be a productive tension between user/User, which we can attend to through the perspective of the becoming-User. These slightly-different terms are somewhat pedantic, to be sure, but are useful. > However, one group, the US government, had a very clear perspective on what it meant to be a Tik Tok User. They viewed TikTok as dangerous, and its users were perceived to be at risk. The nature of this risk, however, remained ambiguous. The Trump administration made several attempts to address this perceived threat. In July 2020, then-President Trump announced plans to ban the app, although the legal authority under which he intended to do so was unclear. Subsequent months saw speculation that ByteDance, TikTok’s parent company, would sell off portions of the company to a US firm such as Microsoft or Oracle. These deals fell through, primarily because ByteDance wanted to keep their recommendation algorithm proprietary. <This is the “secret sauce” – what makes Tik Tok really profitable> In August 2020, Trump issued an executive order aimed at banning TikTok, which was later challenged in DC District court in September 2020. The court ruled that Trump did not have the authority to unilaterally ban the app, although the issue eventually became moot when Biden rescinded the executive order. This was hardly the end of the United States’ attempts to wrangle the platform. The Biden administration also took several steps to restrict TikTok. For instance, the app was banned on any devices owned by the federal government. Many universities receiving federal funding and local governments followed suit by enacting similar rules. On April 24, 2024, Biden signed the Protecting Americans from Foreign Adversary Controlled Applications Act (PAFACA), which requires ByteDance to <sell portions of the TikTok platform to a US-based company>. The earliest this could go into effect was January 19, 2025, but it was immediately challenged. Why has the US government been so set on banning Tik Tok? In the debates and national discourse surrounding these events, people have brought up many concerns: <data tracking, concerns about ByteDance’s close connection to the CCP>. Secondary concerns include potential health risks (e.g. young people spending so so so much time on the app. Ultimately, the underlying rationale for these actions is based on largely misinformed fears, likely fueled by Sinophobia as well as racism. Many critics have pointed out the hypocrisy of these actions, noting that many US companies, such as Meta, are also engaged in widespread data collection and user surveillance. <And US-platforms are arguably just as bad for everyone’s mental well-being>. <Put the “If you wanna steal my data” meme here.> It’s probably pretty clear by this point that I believe that the US TikTok ban is shortsighted and bad policy. I think there’s a pretty clear cut argument for ByteDance to challenge the law, and I don’t expect the app to wholly disappear come January 2025. I’m writing this in the months between the law’s passage and its actual implementation. Readers will likely have the benefit of knowing how this actually plays out. But the specific outcome is not necessarily the main point here: Regardless of what TikTok’s fate ends up being, there will always be these kinds of legal maneuvers to re-shape the internet. And to be clear, that’s not inherently a bad thing. Regulation is good. And standards/protocols, for that matter! But we need to be thoughtful about how they play out. Nevertheless, we cannot ignore its implications and the broader discourse it contributes to regarding the role and perception of “Users” on the Internet. <This Tik Tok ban is yet another example of the disconnect between User and user – and the ways that people navigate this difference coalesces in the becoming-User.>

As you can see, I expanded significantly on many paragraphs, and added sections (in brackets) where I planned to add further signposting and connections to other ideas in my dissertation. This revised version of the section is what my advisor read as part of the full conclusion. His feedback, among other things, was that the conclusion was spending too much time on the Tik Tok example. It felt less like an opening anecdote, and more like setup for a topic that would get substantial discussion, but which never came to fruition in the conclusion. It set up some of the “Big IdeasTM” that I wanted to emphasize in my conclusion, but took far too many pages to get to that point. With that feedback in mind, I trimmed large portions of this section and rearranged much of the text to the point that the final product bears little resemblance to what the AI had initially produced:

Over the last several years, the short-form video app TikTok has become incredibly popular and influential. During the COVID-19 pandemic, millions of people downloaded the app and became TikTok users, transforming the platform into a global phenomenon. The TikTok app incorporates audio and video into an endlessly scrollable feed of algorithmically curated content, and it has become an important way that memes are circulated. Beyond memes, TikTok has been astoundingly influential in numerous ways. It has facilitated the rapid spread of news and information, provided affordances for young people to build and maintain communities, created unfair and unjust conditions for certain communities, supported the spread of misinformation, and has provided a platform for the rapid growth of the “influencer industry,” and has sparked many innovative lines of research, just to name a few examples. Being a TikTok user can mean many things and the app’s cultural significance is continually evolving as the platform introduces new features, ByteDance seeks to support its corporate goals, and as users incorporate these changes into their own daily uses and practices. As media and communications researcher Milovan Savic puts it, TikTok “did not come fully formed, but is instead the result of the dynamic among platform, users, and nonusers.” I might extend this framing to emphasize the difference between how TikTok imagines its Users and how actual people use the app (as users). As I have shown throughout this dissertation, It is not always clear what it means to be a User because there are infinitely many ways that online spaces are encountered by individuals users. There is no singular version of a User, and there can be a productive tension between user and User, which we can attend to through the perspective of the becoming-User. However, for one group, there is a very clear perspective on what it meant to be a Tik Tok User. The US government views TikTok as dangerous and have tacitly adopted the position that its users are at risk and in need of protection. The nature of this risk, however, has remained somewhat ambiguous. The Trump administration made several attempts to address this perceived threat. In July 2020, then-President Trump announced plans to ban the app, although the legal authority under which he intended to do so was unclear. Subsequent months saw speculation that ByteDance, TikTok’s parent company, would sell off portions of the company to a US firm such as Microsoft or Oracle. These deals fell through, primarily because ByteDance wanted to keep their recommendation algorithm proprietary. The highly effective personalized recommendation system is what has made TikTok so widely successful, so it is unsurprising that the company has sought to protect this as a trade secret. But hiding the inner workings of the app has likely only contributed to the government’s growing suspicions. In August 2020, Trump issued an executive order which aimed at banning TikTok in the United States, though this was immediately challenged in DC District court in September 2020. The court initially ruled that Trump did not have the authority to unilaterally ban the app, although the issue eventually became moot when Biden rescinded the executive order. This was hardly the end of the United States’ attempts to wrangle the platform, though. The Biden administration also took several steps to restrict TikTok. For instance, the app was banned on any devices owned by the federal government since 2022. Many universities receiving federal funding followed suit by enacting similar rules, as have state and local governments throughout the country. On April 24, 2024, Biden signed the Protecting Americans from Foreign Adversary Controlled Applications Act (PAFACA) into law, which requires ByteDance to sell portions of the TikTok platform to a US-based company. The earliest this could go into effect was January 19, 2025, but ByteDance did challenge the law almost immediately, leaving the ban’s future uncertain. Why has the US government been so set on banning TikTok? In the debates and national discourse surrounding these events, people have brought up many concerns about ByteDance’s close relationship with the Chinese Communist Party, citing fears that the company could easily access sensitive user data and share it with the Chinese government. Secondary to these privacy concerns, some people have noted the potential mental health impacts, especially as large proportions of young users have flocked to the app. However, user tracking, data privacy, and Sinophobic tropes have largely dominated the discourses surrounding the TikTok ban. While there may be some merit to these speculations over the effect that TikTok has on its users, it is difficult to draw the conclusion that a narrowly targeted ban is the best course of action. Many critics have pointed out the hypocrisy of these actions, noting that many US companies, such as Meta and X, are also engaged in widespread data collection and user surveillance; if there are mental health risks to TikTok, these US companies’ platforms and apps are likely just as dangerous too. The fact that other major platforms have not subject to the close scrutiny that TikTok has encountered suggests differences in how Users of these platforms are conceptualized. The United States TikTok ban is yet another example of the disconnect between User and user, and the ways this difference coalesces in the subject position of the becoming-User. But if governments and regulators uncritically follow a narrow conception of what it means to use the internet, they may contribute to the creation of an online space that does not meet everyone’s needs and experiences equitably. They might, for instance, pass a law that seeks to ban a single platform (TikTok) rather than imagining a broader protection of data rights and privacy across all online contexts—something more akin to the approach of what the European Union accomplished with the GDPR and the DSA. The end result of such narrow thinking on what it means to be a User is that we simply re-create and extend the same conditions that have already existed, complete with their imperfections and inequalities. The United States TikTok ban is shortsighted because it assumes a singular version of what the platform is for its users rather than acknowledging the multiple meanings it may hold and by doing so, it positions users as powerless. The TikTok ban falls in line with one version of what the Internet can look like, in which governments and companies do things to, and we are mostly powerless us as users. This is not the kind of Internet that I want, and thankfully it doesn’t really ring true for how the actual internet is experienced. The case studies that I have described throughout the previous chapters show how the becoming-User can illuminate some of the other dimensions and characteristics which exist—and thus make a different kind of online world for ourselves.

I also can't pass up the opportunity to do a bit of shitposting as part of my writing, so in the final version of the conclusion, I worked this meme into the above section:

So what did I learn from this entire process? Is generative AI all that useful as a writing tool? Well, maybe. But perhaps not in the way that many people may expect it to be, and most definitely not in the ways that over-played fears of AI “replacing” humans seem to suggest. As I was working on editing and completing my dissertation’s conclusion, I never really felt the need to turn back to Copilot to iterate on its original output, or to generate more “raw materials” for me to work with. As I mentioned earlier, I really just needed something to work with, and transforming my outline into prose was really all I needed to truly get started. Having gone though this process, I feel confident in saying that I don’t find much utility in using AI generated text as-is. The actual text which gets generated is simply not especially useful at face value.

Even after providing significant input (the outline that I had drafted) and adding further context (in the lengthy prompt I provided), the output text still misses so much detail and nuance and thus was not able to be immediately incorporated. It still required significant editing, reworking, and further additions before I was satisfied with how well the text communicated my ideas and arguments. That’s all to say I don’t anticipate generative AI replacing the time and labor that I put into writing, which is okay! After all, the work of writing enables me to think through my ideas, and is as significant part of my research process as close reading and textual analysis. I’m glad that AI won’t be replacing this large aspect of my work any time soon, but I’m even happier to have an idea of how the tools that are being developed could fit within my work. Like all writers, I struggle with writer’s block and find it difficult to move forward with certain parts of the process. If AI can help me overcome such hurdles (such as by turning an outline into prose) and let me focus on the fun parts of the process (figuring out how to use that prose to communicate), then that’s all the more better in my mind.

Return to Blog